This was a paper published during my Ph.D. which I presented at the Humanoids 2019 conference in Toronto, Canada.

Abstract

A Probabilistic Movement Primitive (ProMP) defines a distribution over trajectories with an associated feedback policy. ProMPs are typically initialized from human demonstrations and achieve task generalization through probabilistic operations. However, there is currently no principled guidance in the literature to determine how many demonstrations a teacher should provide and what constitutes a “good” demonstration for promoting generalization. In this paper, we present an active learning approach to learning a library of ProMPs capable of task generalization over a given space. We utilize uncertainty sampling techniques to generate a task instance for which a teacher should provide a demonstration. The provided demonstration is incorporated into an existing ProMP if possible, or a new ProMP is created from the demonstration if it is determined that it is too dissimilar from existing demonstrations. We provide a qualitative comparison between common active learning metrics; motivated by this comparison we present a novel uncertainty sampling approach named “Greatest Mahalanobis Distance.” We perform grasping experiments on a real KUKA robot and show our novel active learning measure achieves better task generalization with fewer demonstrations than a random sampling over the space.

Please see the paper for details on this work.

@inproceedings{conkey2019active,

title={Active Learning of Probabilistic Movement Primitives},

author={Conkey, Adam and Hermans, Tucker},

booktitle={2019 IEEE-RAS 19th International Conference on Humanoid Robots (Humanoids)},

pages={1--8},

year={2019},

organization={IEEE},

url={https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9035026}

}

Software Development

This project involved a few interesting software development efforts to implement the required tooling for recording human demonstrations on the robot, visualizing the environment to aid user engagement, and executing policies in an efficient way.

| Repository | Description |

|---|---|

| ll4ma_movement_primitives | Custom implementation of ProMP policies and the infrastructure needed to execute them on a robot. |

| ll4ma_robot_control | Real-time control framework with controller switching capabilities. Note: the LBR4-specific code is unfortunately a private repo for the lab. |

| robot_aruco_calibration | Code for performing camera-to-robot calibration using ArUco fiducial markers. |

Gravity Compensation Controller

I needed to record human demonstrations of the task on the robot using a technique call kinesthetic teaching. This is a simple technique where the human physically takes hold of the robot and guides its motion to complete the task at hand. It has its pros and cons, but for the simple task in this paper it was a good choice.

It is common to use a gravity compensation controller for the robot, which is a model-based controller that computes the motor torques required to keep the robot from falling to the ground as it would otherwise tend to do under the influence of gravity. This is a fun control mode because it means the robot is free to move about when a human user grabs hold of its links and moves it around, it feels as if the robot is weightless in spite of it being quite heavy! While several robots come with a gravity compensation mode (including the KUKA LBR4 robot I used), this was going to impractical for my purposes as I was going to have to constantly switch the pendant mode between giving a demonstration and having the robot execute trajectories autonomously. This was also going to require a software restart on our PC each time the autonomous controller was restarted. I wanted a better way, since I knew I was going to record many demonstrations in each session.

The control workflow I needed was:

1. Put robot in gravity compensation mode

2. Provide a kinesthetic demonstration of the task

3. Put the robot in autonomous mode

4. Execute a trajectory autonomously to return the robot to a home position

5. Either do another demonstration, or execute a policy autonomously

So, I wrote my own control framework! I built off some of our lab’s existing control infrastructure written in C++ using the Orocos Real-Time Toolchain. This was a complete refactor to support multiple controller modes that could be switched between using a ROS service call. This enabled me to seamlessly switch between teaching and autonomous modes with a simple software hook.

Another fun aspect of this is the user interface. I initially developed a makeshift GUI to control a session. It was not pretty, but it got the job done. However, I found myself going back and forth between the computer and the robot repeatedly, it would get dizzying doing a demonstration session. I decided to hook up an X-Box controller to the PC, and use the registered button presses to switch between the different robot control modes. I could:

1. Press a button to start recording data and enter gravity compensation mode

2. Provide a kinesthetic demonstration of the task

3. Press a button to stop recording and save the data, and enter autonomous mode

4. Press a button to have the robot return to a home position

This enabled me to stay near the robot recording one demonstration after another without having to return to the PC, making it drastically more efficient to record the data I needed for testing and experiments.

Environnment Calibration

For experiments and data collection on the robot, I required a method to calibrate the pose of the camera with respect to the robot, i.e. calibrate the extrinsics of the camera. Our lab initially had a method for doing this that required attaching a calibration checkboard as the robot’s end-effector, and manually jogging the robot through a sequence of about 20 different configurations to determine the camera pose with respect to the robot. This process was unsatisfying because it would take about 20 minutes to perform, it would still require small manual adjustments after completion, you’d have to remove the robot hand and mount the checkerboard each time you do it, and if you accidentally bump the camera, you have to start all over! I needed a better way.

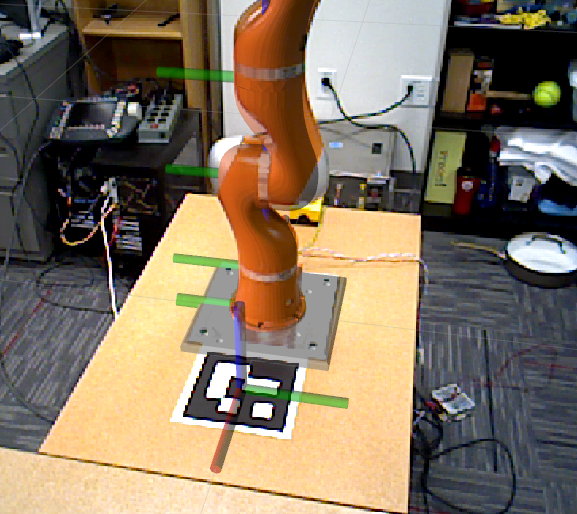

My solution was simple and effective: Use an ArUco fiducial marker and a slightly modified version of an open source detector simple_aruco_detector to perform the calibration. I placed a large ArUco marker in a known location with respect to the robot’s base (I just manually measured the offset), ensured it was in view of the camera, and boom you can quickly determine the pose of the camera in the robot’s base frame. I developed a package robot_aruco_calibration to make this process quick and painless, with an rviz visualizer for validating its correctness.

The speed and ease of re-calibration proved crucial in my experiments. I could freely adjust the camera pose to get the best angle for my experiments and demo videos. An unfortunate issue I also had was that the robot would occasionally drop the object, which was a heavy drill, and it would bump the camera tripod and ruin my calibration! Thanks to my calibration approach, I just had to run a quick script to regain the calibration and I was back in business without any downtime. Had this happened with our old calibration approach, I would have to spend 20-30 minutes each time the calibration was disturbed.

This also enabled me to set the pose of the table in environment so that I could visualize a mesh of the table in rviz. This would provide further confidence the calibration was correct, but also enabled me to visualize the full environment in rviz which helped a lot in object placement during experiments.

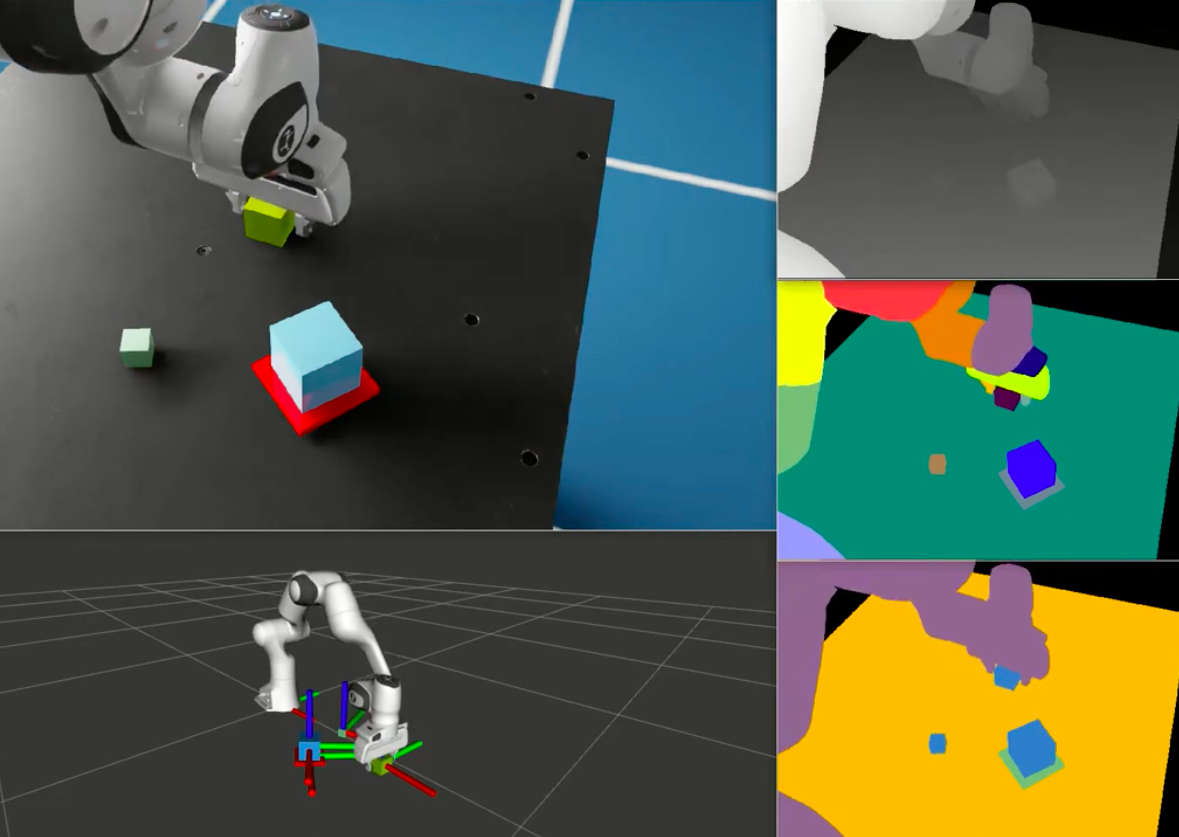

Visualizations

An important aspect of this project was having informative visualizations of the environment. I needed to place the object in random poses on the table for experiments and data collection. I wanted this to be unbiased, i.e. I didn’t want to pick poses I thought were random, I wanted them to be truly randomly generated. I solved this using a method for random pose selection, and then rendering that pose in rviz using a coordinate frame together with a mesh of the object visualized with a Marker. I also used Marker primitive shapes to overlay on the table to ensure my camera-to-environment calibration was correct.

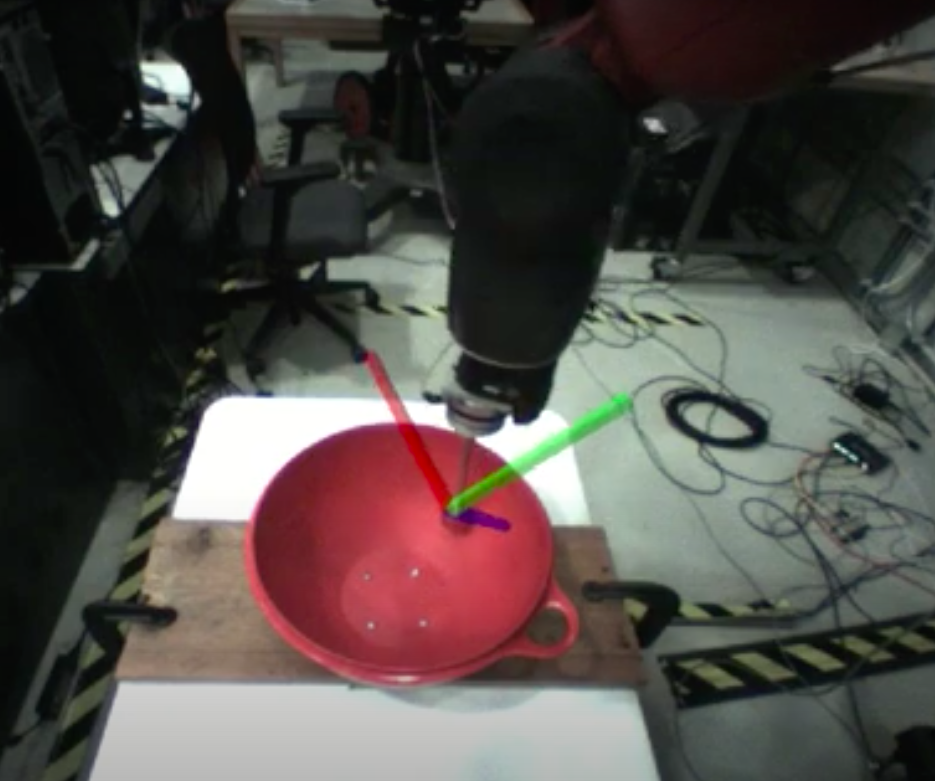

A cool feature is I used an open source Bayesian object tracker dbot_ros from the talented folks at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems to track the pose of the object in real-time. This made it extremely easy to put the object on the table and move it around until its pose matched the target pose.

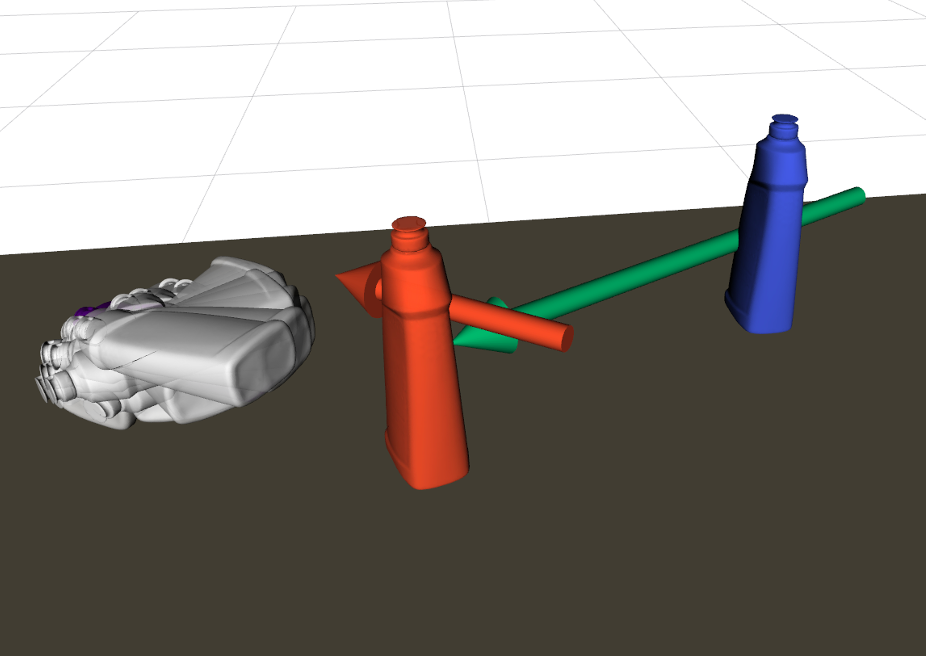

I also had a desire to visualize trajectories generated from the ProMP policies. This was a sanity check since they were going to be executed on the real robot, and they’re probabilistic in nature, I wanted to ensure that samples from the trajectory distribution weren’t going to do anything crazy on the robot. I used Markers again together with a RobotModel in rviz to generate trajectory previews overlayed on the real camera feed. This gave me confidence that when I executed a trajectory, it wasn’t going to collide with the table or the object, or do anything else unexpected.