The last project I worked on during my Ph.D., Planning under Uncertainty to Goal Distributions, involved learning robot skills from demonstration data. The other projects I had worked on involved learning from human demonstration data, but that was not an option for this project – we needed a HUGE amount of data. Instead of having a human provide thousands and thousands of demonstrations, we wanted a way we could record data of the robot performing the tasks in an unsupervised way.

Our solution was to engineer some behaviors using simple task specifications and motion-planned trajectories to execute them. This could have been done on the real robot, but that was also going to involve a fair amount of babysitting by a human. The solution was to record the data in simulation. But collecting data from just one simulator was going to take a really long time. The even better solution was to run many simulations at once! And fortunately, I was working on this at the advent of NVIDIA’s Isaac Gym, which enabled running hundreds of simulations at once on a desktop computer (note Isaac Gym has since been deprecated, in favor of NVIDIA’s Omniverse stack).

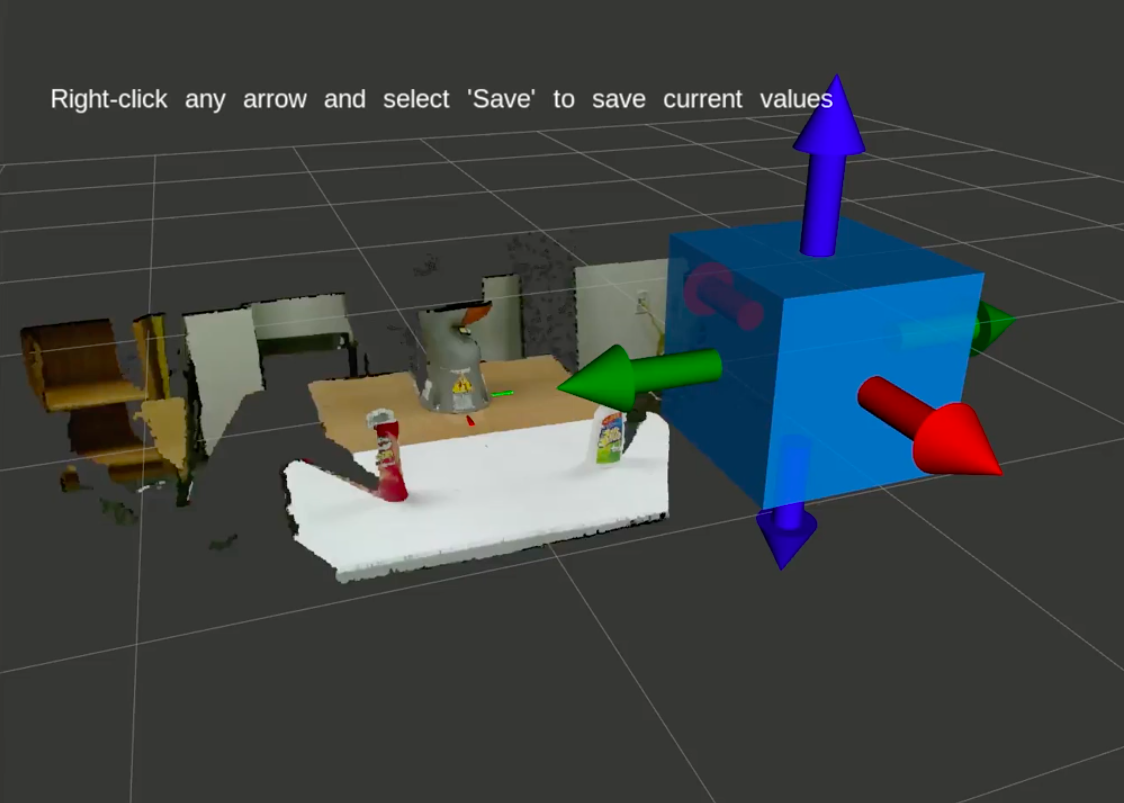

I developed a framework for mass data collection of robot skill executions in Isaac Gym. This was a huge undertaking which I spent much of the COVID pandemic lockdown toiling away on. It required thoughtful system engineering to develop the infrastructure for skill definition and execution, configuration of the simulation environments, recording and managing multimodal datasets, and running it all autonomously for days at a time.

I’ll point out some of the core software components that I think are of interest.

Software

| Repository | Description |

|---|---|

| ll4ma_isaac | Core repository for robot behavior data collection in Isaac Gym. |

| ll4ma_moveit | Interface to simplify requesting motion plans from MoveIt. |

| ll4ma_util | Suite of utilities for all sorts of things including file handling, ROS utilities, data processing, CLI helpers, etc. |

Behaviors

Behaviors are hierarchical in the sense that a behavior, e.g. pick up an object and place it, can be composed of more simple behaviors like a “pick up object” behavior and a “place object” behavior. Even an object-picking behavior is hierarchical with constituent steps of moving through free space near the object, grasping the object, and lifting it. The Behavior class manages the hierarchical composition of behaviors and determines transitions between behaviors using the environment state as well as the state of the behaviors themselves. For example, if the robot gripper is sufficiently close to an object it knows it can now try to grasp it. And if a behavior fails, e.g. the object is dropped, it can halt the behavior or take some remedial action.

One simple base behavior is MoveToPose, which enables the robot to move to a desired configuration in joint space or move its end-effector to a desired 6-DOF pose in Cartesian space. This behavior is a sub-behavior of nearly all other more complex behaviors. As long as you have some way of setting targets for the robot to move to you can get a lot done with this behavior. For example, in the PickObject behavior, target end-effector poses are set with respect to the object’s coordinate frame, which in simulation can be read from the simulation state and in the real world can be acquired using a variety of object pose estimation techniques. Knowing the object’s pose together with a target end-effector pose in the object frame lets you compute a target pose for the robot in the world frame, which the robot can then move to using the MoveToPose behavior.

To give you a sense of the hierarchy involved in a more complex behavior, consider StackObjects which allows the robot to build up a stack of objects, i.e. build block towers. The behavior hierarchy looks like this:

StackObjects

PickPlaceObject_1

PickObject_1

MoveToPose_approach

CloseFingers

MoveToPose_lift

PlaceObject_1

MoveToPose_above

MoveToPose_place

OpenFingers

...

PickPlaceObject_N

It’s a powerful feeling to be able to construct complex behaviors once you have the more basic component behaviors in your toolbox. In fact, the object-stacking behavior was not one I was using, one of my labmates wanted it for his experiments and I thought, well it’s really just a sequence of multiple pick-place executions, I can make that behavior with what I already have!

You might be wondering how hard it is to setup these behaviors. After all the legwork in the code, from the user perspective it’s actually really easy! Just a simple YAML config:

# ============================================================================== #

#

# This config specifies a task for the iiwa+reflex to stack a tower of 3 blocks.

# If base_obj_position is specified in the behavior, it will first move the base

# block to that position then stack from there, otherwise it will keep the base

# block as it is and just stack the other block.

#

# ============================================================================== #

task:

task_type: stack_objects

behavior:

name: stack_objects

behaviors:

- behavior_type: StackObjects

name: stack_objects

objects: [block_1, block_2, block_3]

ignore_error: True

allow_side_grasps: False

remove_aligned_short_bb_face: True

stack_buffer: 0.0

extra_steps: 200

env: ~/isaac_ws/src/ll4ma_isaac/ll4ma_isaacgym/src/ll4ma_isaacgym/config/env_configs/iiwa_3stack.yaml

Some of those params are less intuitive at first glance, but they provide extra customization to your use case. For example, allow_side_grasps: True would expand the permissible grasp configurations of the robot to include grasping the object from the side instead of a top-down grasp. Disabling can be useful for building block towers, but if the tower’s high enough you might need to enable it so that you still get kinematically feasible trajectories for stacking the higher blocks.

I won’t go into details on how all these params work, but the fact that you can specify 10 or so lines of YAML config and produce meaningful manipulations with a robot, that’s pretty awesome!

MoveIt Integration

I wanted to use motion-planned trajectories as a core part of the behavior motions since moving through free space without collision is fundamental skill for a robot to have in its repertoire. Motion planning methods are also well-studied with existing implementations so it was a low-effort way to get high-quality motions in my data collection framework.

I chose to use MoveIt since it is the standard tool to use in ROS and has access to many of the Open Motion Planning Library (OMPL) algorithms as well as some more modern techniques like CHOMP and trajopt. I was already quite familiar with MoveIt, but I felt there was a lot of boilerplate setup I had to do each time I wanted to compute a trajectory, and everytime I had to fumble through the documentation to figure out the right way to initialize things and parameters to set. I wanted a way to standardize my calls to MoveIt so I could simplify the workflow and reduce boilerplate on the client side (i.e. in my data collection framework).

I developed a simple package called moveit_interface within our ll4ma_moveit repository. Its main responsibility was to provide a simple ROS service that could be called to compute motion plans (joint space and task space), and compute commonly used things like Jacobians and forward and inverse kinematics. The package was written in C++ because the C++ API for MoveIt was more feature-complete and configurable than their Python API.

In my behavior framework I created a get_plan function that would make the ROS service calls to the MoveIt interface to retrieve the desired motion plan. Whether I wanted a joint space trajectory (e.g. useful for moving to be near an object), or a task space trajectory (e.g. useful for moving the end-effector in a straight line to a pre-grasp location), I just had to set some flags on the service request and I would get a trajectory to execute!

This capability was at the core of the MoveToPose behavior, which was used as a building block every behavior I defined for data collection. It was really nice to have such an easy interface to computing trajectories for simple motions.

Data Logging

Recording datasets was the sole reason I had setup any of this up to begin with. In the long-term I was interested in learning robot behaviors from data of all different modalities - images, point clouds, forces and torques, poses, robot joint positions, etc. I wanted to get as much data out of the Isaac Gym simulations as I possibly could. Unfortunately this kind of data logging wasn’t really built in to Isaac Gym in any meaningful way. I was going to have to figure out a way to extract all that data myself and manage it in some coherent way.

In order to get at the data at all, I had to incorporate the logging at the level of stepping the physics engine in the simulator. The process flow was:

1. Have the robot take an instantaneous action.

2. Step the physics engine.

3. Record data resulting from that step in the simulation.

This actually served as a nice instantiation of the formalism of partially observable Markov decision processes (POMDPs) which is at the core of the theory behind embodied intelligent systems: Take an action, update the environment state, get an observation.

Having to log the data myself at the level of stepping the physics engine actually gave me a lot of control and flexibility, I could choose which modalities I wanted to log, when to log them, and how to save the data.

Data Modalities

I tried to grab every data modality offered by Isaac Gym, so the generated datasets included the following:

1. Robot joint state

- Positions

- Velocities

- Torques

2. Robot end-effector state

- Position

- Orientation

- Velocity

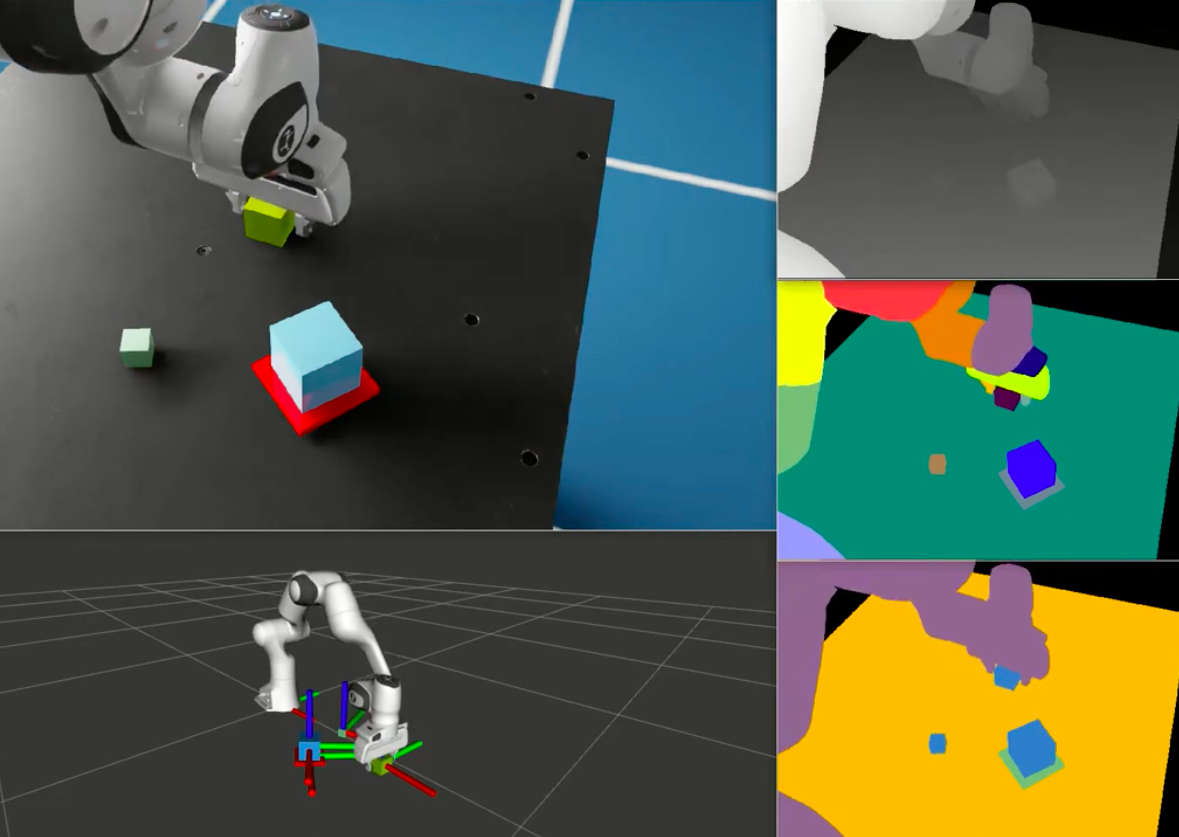

3. Images

- RGB

- Depth

- Instance segmentation

- Optical flow

4. Object state

- Position

- Orientation

- Velocity

5. Environment contacts

6. Target joint state

7. Discrete end-effector action state (e.g. open/closed)

8. Auxiliary data

Some interesting notes:

- The auxiliary data enabled behaviors to log any additional data that might be useful in the dataset. One thing I had all behaviors log was a string representing the current behavior hierarchy. This enabled easy correlation of environment data to the current higher-level action being applied.

- Isaac Gym offered instance segmentation masks and optical flow as retrievable data. This is very cool! Typically that’s something you’d have to compute yourself, and here you could just access it like any other image data.

- In simulation you can get far more ground-truth information than you could ever get in the real world. For example, the environment contact data would tell you which objects were in contact with other objects in the environment, even when they’re not observable in a camera image. That is incredibly useful information. This is a neat feature of learning from simulation data, and you can utilize it to supervise learning in hopes of achieving sim-to-real transfer of your learned policies.

Logging Modes

I supported two different modes of data logging:

- Record everything always!

- Record data only at the transition points between sub-behaviors.

The former was desirable for having a complete dataset of the entire behavior execution, but came at the cost of having a HUGE dataset to keep around. If all image modalities were saved for every timestep you’d end up with many gigabytes of data just for one execution. Once you start accumulating multiple executions for a dataset it really starts to put a burden on your hard drive (I actually maxed out my main hard drive at one point because I accidentally set the wrong drive to save to and it crashed my computer on an overnight run). Such fine-grained data would be useful for low-level policy learning, but mode (2) was more useful for my purposes in doing skill learning. I mainly cared about what happened at the transitions between behavior executions. This is a huge benefit of skills: they effectively form a higher-level action space, abstracting away from the low-level timestep transitions. You need less data to learn them, and they better support long-horizon planning.

Data Format

I chose a relatively simple format for saving the data. I had in the past experimented with proper logging formats like HDF5 but had been bitten by corrupted data, and I wasn’t interested in needing special libraries or viewers for interacting with my data. I decided to store everything as a numpy array in a dictionary keyed by the data type. The dictionary of data was then compressed and saved using pickle.

Arrays were needed since the data was temporal, and having them as numpy arrays made the data simple to work with downstream for learning in PyTorch. Using pickle enabled at least some compression to keep file sizes small. A dictionary for the top-level structure made the data extensible, as it would be easy to augment later on if additional data is post-processed offline (e.g. filtering force data or computing pose transformations to a new reference frame).

Overall I was quite happy with these choices, it kept things organized and intuitive and was easy to work with for model training and visualizations. I had the luxury of a terabyte local drive and effectively infinite storage in the cloud through the university so I didn’t have to worry too much about generating huge datasets. I would also pre-process the raw data into smaller sample files when it was time to do model training, which would ensure I wouldn’t have to load large files at training time, thereby speeding up learning significantly.

Real Robot

You might be thinking, Adam, this is all well and good, but it’s just a simulation! What if I wanted to run the behaviors on a real robot?

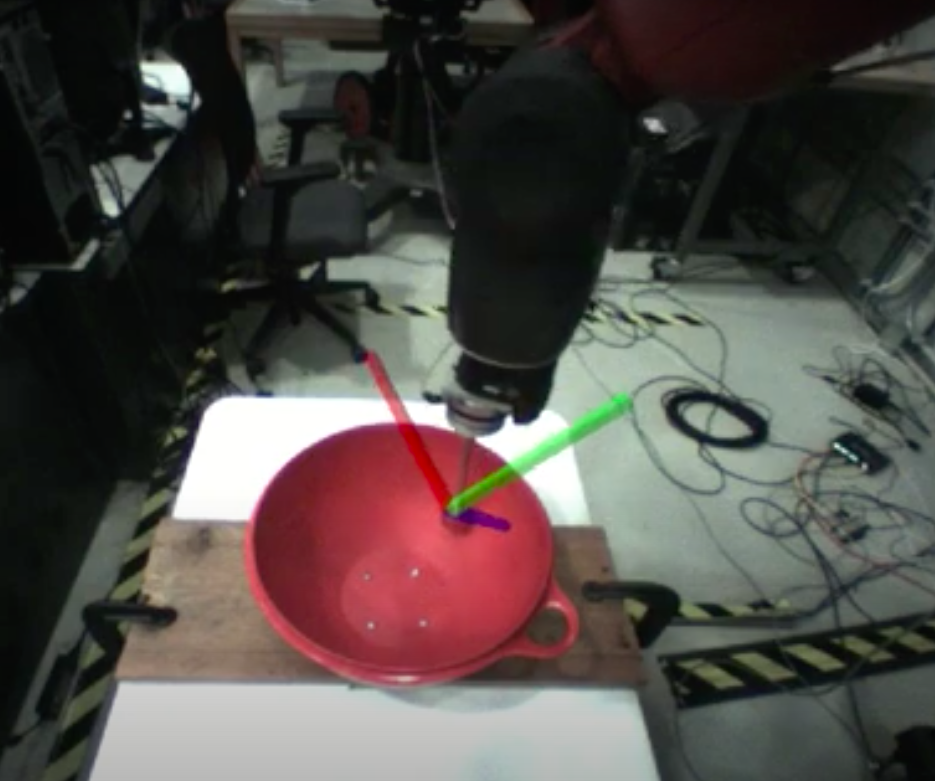

You’re not going to believe this, but you can do that too! And I did! My objective in my paper was to learn high-level skills in simulation that would transfer to the real robot. This was feasible since the skills were parametrized by object pose, and I was using motion-planned trajectories for executions. If I could get object poses in the real world, I could use the same MoveIt interface I used in simulation to generate motion plans on the real robot.

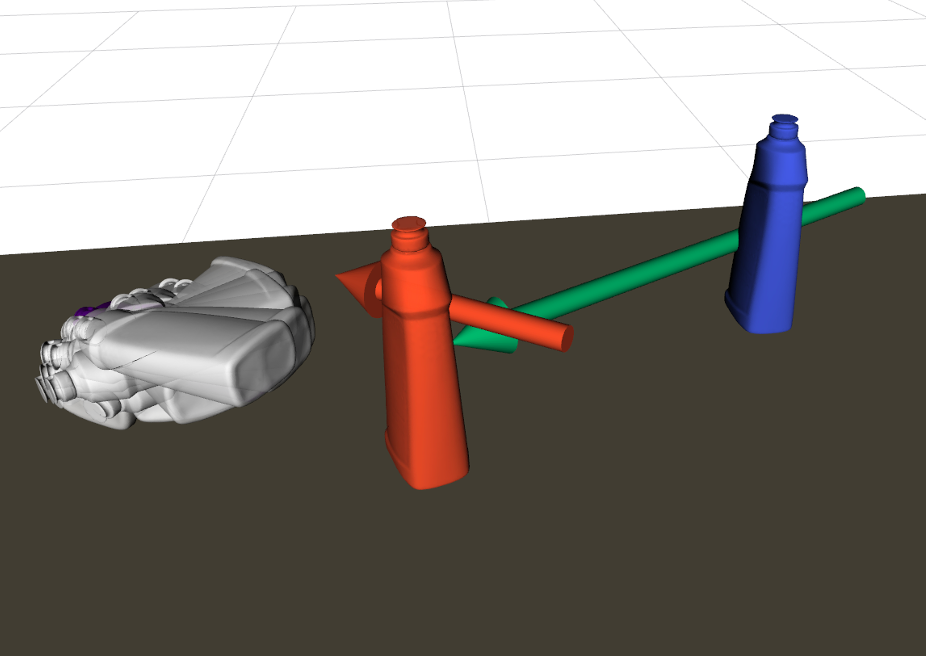

Any pose estimation technique could work, and there are truly many of them. In the several years since I worked on this project, there have been several newer methods come out that look even more impressive. I used NVIDIA’s Deep Object Pose Estimation (DOPE) because it was relatively easy to get running in our lab and it did a very good job on the objects we were using.

Here is one example of executing the PickObject behavior:

My labmate Yixuan Huang built off of this framework to do experiments for a couple of his papers involving multi-object manipulation:

- Latent Space Planning for Multi-Object Manipulation with Environment-Aware Relational Classifiers

- Planning for Multi-Object Manipulation with Graph Neural Network Relational Classifiers

I encourage you to check out his work here for some more examples of real-robot executions of the PushObject and StackObjects behaviors, and have a look at his newer publications which are really impressive!

Summary

I used my data collection framework to collect thousands upon thousands of instances of the robot performing various manipulation tasks like picking and placing objects, pushing objects, stacking objects, etc. I could run many simulations concurrently in Isaac Gym and I set it up such that a session would continually save the data from each execution and reset the environment with a new simulation.

The data collection script would run for many hours unsupervised, so I could start data collection before I left the lab for the night and come back in the morning to a rich dataset to do learning on. I also ran it on a GPU cluster and across multiple machines in our lab, meaning I was generating a staggering amount of data, all in the background while I was doing other things like setting up deep learning models for training and writing my dissertation. That is the real payoff of all that engineering effort I put into it.

It was certainly not without faults and limitations, and there was much I would have improved about it if I had continued to work on it, but once I graduated I left it in the capable hands of my labmates who continued to build upon it and use it to do experiments for their own publications. It provided me the data I needed to finish my dissertation, and gave us some sensible infrastructure for running simple tasks on the robot in the lab. Overall it was a substantial software engineering task that required me to be thoughtful about design, data management, and scalability – and it was a lot of fun to work on!