This was a paper I worked on during my Ph.D. I did not get it published, but it is up on arXiv and served as a culminating piece of my Ph.D. dissertation.

Abstract

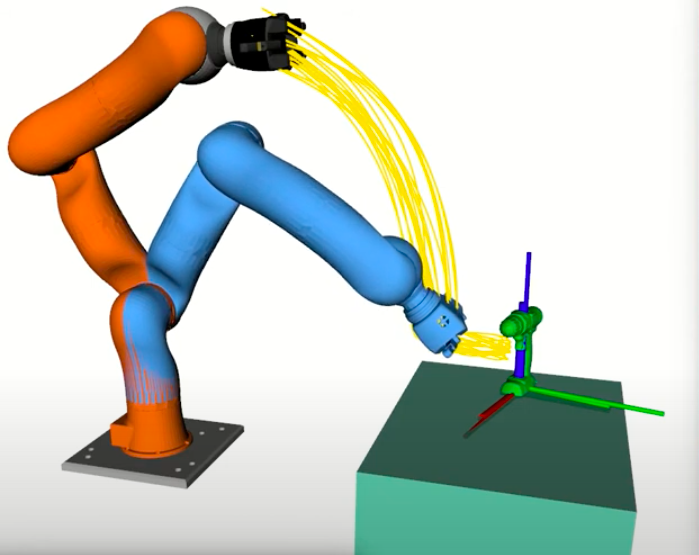

Goals for planning problems are typically conceived of as subsets of the state space. However, for many practical planning problems in robotics, we expect the robot to predict goals, e.g. from noisy sensors or by generalizing learned models to novel contexts. In these cases, sets with uncertainty naturally extend to probability distributions. While a few works have used probability distributions as goals for planning, surprisingly no systematic treatment of planning to goal distributions exists in the literature. This article serves to fill that gap. We argue that goal distributions are a more appropriate goal representation than deterministic sets for many robotics applications. We present a novel approach to planning under uncertainty to goal distributions, which we use to highlight several advantages of the goal distribution formulation. We build on previous results in the literature by formally framing our approach as an instance of planning as inference. We additionally derive reductions of several common planning objectives as special cases of our probabilistic planning framework. Our experiments demonstrate the flexibility of probability distributions as a goal representation on a variety of problems including planar navigation among obstacles, intercepting a moving target, rolling a ball to a target location, and a 7-DOF robot arm reaching to grasp an object.

Please see the arXiv paper for details on the research.

@article{conkey2020planning,

title={Planning under Uncertainty to Goal Distributions},

author={Conkey, Adam and Hermans, Tucker},

journal={arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.04782},

year={2020},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.04782}

}

Software

| Repository | Description |

|---|---|

| distribution_planning | Core repository for distribution-based planning algorithms and infrastructure. |

| multisensory_learning | Repository for deep learning algorithms used in planning framework (e.g. mixture density network) |

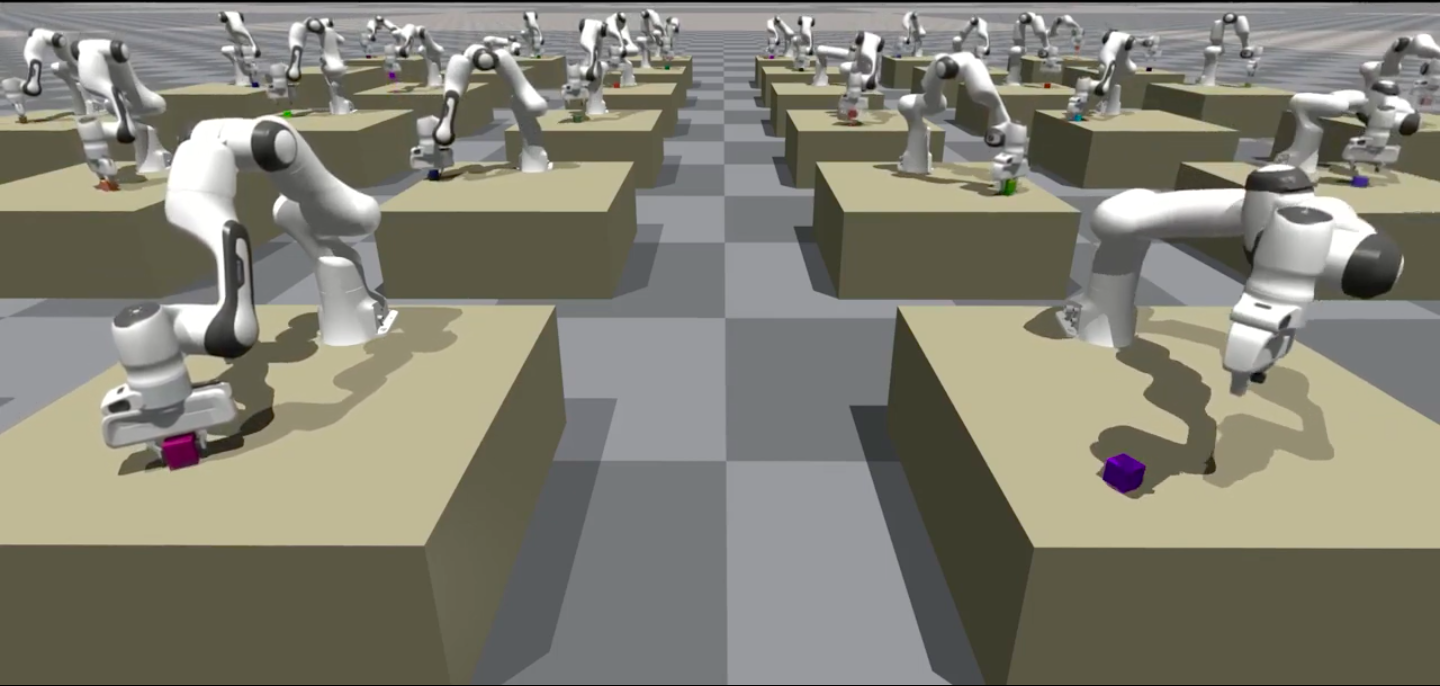

| ll4ma_isaac | Core repository for robot behavior data collection in Isaac Gym. |

| ll4ma_moveit | Interface to simplify requesting motion plans from MoveIt. |

| ll4ma_util | Suite of utilities for all sorts of things including file handling, ROS utilities, data processing, CLI helpers, etc. |

What is a goal distribution?

A goal distribution is nothing more than a probabilistic interpretation of a target. If you consider what goals look like in many problems in robotics, they are typically point-based – move to this target pose, track to this setpoint in the robot’s joint space. Even if the task specification is higher-level (e.g. navigate to the living room), there will often be a lower-level point-based target it resolves to.

Goal distributions are a broader view of goal spaces. Formally they subsume point-based goals (e.g. with a Dirac-delta function), but can further encode uncertainty about the goal (e.g. a Gaussian distribution or uniform random). For example, the goal of “navigate to the living room” could be well-encoded by a uniform random distribution over the valid poses the robot could exist within the living room – you want the robot to be in that room but specify no preference on where it should be within the room. You could further encode preference, e.g. as a Gaussian distribution or a mixture of Gaussians.

We have a lot of details in the paper about our conception of goal distributions and how that interpretation is useful in robotics. The key takeaway is that it is a more flexible notion of a goal that can encode uncertainty about the goal, and it can integrate well with probabilistic methods already used in robotics, e.g. uncertainty propagation in state estimation.

Why work on this?

It’s easy to question the utility of this paper, and believe me, reviewers did! What do we get out of goal distributions that we don’t ultimately get from point-based goals and more traditional goal formulations? On some level, it’s a fair criticism, but there was a kernel of intrigue in our idea that made me feel we were onto something.

Typically in robotics (and life generally) we are averse to uncertainty. While we might strive to reduce uncertainty as much as we can, there is an inherent limit to it. Robots (and humans) in the real world have to perform their tasks in spite of imperfect knowledge, imperfect task execution, and even imperfect task specification. What intrigued me, is what if we don’t necessarily try to reduce the uncertainty as much as possible, but embrace the uncertainty we have, and even try to leverage it to our advantage?

As a concrete example, consider a robot that is tasked with sorting recyclable materials. Suppose a conveyor belt of objects is streaming by the robot and it has to pick up objects as they go by, and put them into a bin based on its type, e.g. one bin has plastic bottles, another aluminum cans, another cardboard, and so forth.

One approach would be to have the robot pick up each piece and place it into the bin. You might have a predefined spot where it should move to over the corresponding bin and drop it in. Fair enough. Now suppose we want to increase throughput dramatically, and picking and placing has reached its limit. What if instead of a careful place action, we have the robot just huck the object into the bin? You have to imagine if we gave a human this task, that’s precisely what they would do! Once they have a hold on the object they would make a split-second decision on where it needs to go and initiate a well-honed motor skill to toss the object in the appropriate bin.

A key thing to note about the second approach, is it increases the uncertainty of where the object will end up. The careful pick and drop into the bin makes it most likely the object will end up in the bin. Executing fast but more reckless tosses means some objects might hit the rim of the bin if the toss wasn’t judged well, or it might hit another object that’s already in the bin too hard and bounce out. But, if we’re getting say a 5x increase in throughput, we might accept the lower accuracy in favor of doing the task faster. We’ve increased uncertainty in the object’s end state, but we accept it to work faster.

I found this basic thought neat, and I think it’s widely applicable. Many tasks can be done carefully, seeking perfect state estimation, perfect execution, trying to adhere as close as possible to the perfect trajectory and perfect objective. Some tasks require this, e.g. robotic surgery. But other tasks we can get away with being a little sloppy. If we cut loose a bit, accept the imperfection, the noise, the sub-optimal, we can still get pretty far in what we’re doing and can potentially go much, much faster.

Our paper was only a tip of the toe in this water, but I think there’s a lot of really cool work that can be done in this direction. The formalism we present in the paper was intended to open the door for this way of thinking about objectives in robotics so that we might be able to pursue more ambitious robotics tasks going forward.